about 2900 B.C. This tool was subjected to chemical analysis and was found to contain combined carbon, which suggests that it may have been composed of steel.

By 666 B.C. the process of casehardening was in use for the edges of iron tools, but the story that the Egyptians had some secret means of hardening copper and bronze that has since been lost is probably without foundation. Desch has shown that a hammered bronze, containing 10.34 per cent of tin, is considerably harder than copper and keeps a cutting edge much better.

Of the other non-precious metals, tin was used in the manufacture of bronze, and cobalt has been detected as a coloring agent in certain specimens of glass and glaze. Neither metal occurs naturally in Egypt, and it seems probable that supplies of ore were imported from Persia.

Lead, though it never found extensive application, was among the earliest metals known, specimen having been found in graves of pre-dynastic times. Galena (PbS) was mined in Egypt at Gebel Rasas (‘Mountain of Lead’), a few miles from the Red Sea coast, and the supply must have been fairly good, for when the district was re-worked from 19I2 to 1915 it produced more than I8,000 tons of ore.

Gold

The vast quantities of gold amassed by the Pharaohs were the envy of contemporary and later sovereigns. Though much was imported, received by way of tribute, or captured in warfare, the Egyptian mines themselves were reasonably productive.

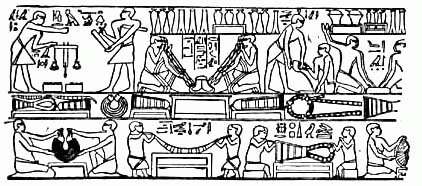

Egyptian Goldsmiths Washing, Melting and Weighing Gold Beni Hasan, 1900 B.C.

Over one hundred ancient gold workings have been discovered in Egypt and the Sudan, though within the limits of Egypt proper there appear to have been gold mines only in the desert valleys to the east of the Nile near Ikoptos, Ombos and Apollinopolis Magna.

Of one of these mines – possibly near Apollinopolis – a plan has been found in a papyrus of the fourteenth century B.C., and the remains of no fewer than 1,300 houses for gold-miners are still to be seen in the Wadi Fawakhir, halfway between Koptos and the Red Sea. In one of the treasure chambers of the temple of Rameses III, at Medinet-Habu, are represented eight large bags, seven of which contained gold and bear the following descriptive labels.

The Egyptian word for gold is nub, which survives in the name Nubia, a country that provided a great deal of the precious metal in ancient days. French Scientist Champollion regarded it as a kind of crucible, while Rossellini and Lepsius preferred to see in it a bag or cloth, with hanging ends, in which the grains of gold were washed – the radiating lines representing the streams of water that ran through.

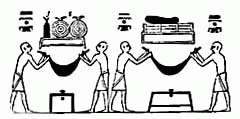

Gold Washing in Ancient Egypt

Crivelli has more recently advanced the theory that the gold symbol is the conventional sign for a portable furnace used for the fusion of gold, and that the rays represent the flames, which, ‘as can be observed in the use of this type of furnace, are unable to ascend because the wind inclines them horizontally’.

In the later dynasties, the Egyptians themselves forgot the original significance of the sign and drew it as a necklace with pendent beads. Elliot Smith however says that this was the primitive form and became the determinative of Hathor, the Egyptian Aphrodite, who was the guardian of the Eastern valleys where gold was found.

Egyptian Goldsmith Workshop in the Pyramid Age

The gold mines in Nubia and other parts of the Egyptian empire seem to have been very efficiently designed and controlled, though with a callous disregard for the human element employed.

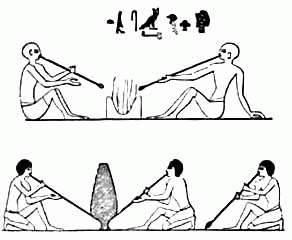

Alluvial auriferous sand was also treated, a distinction being made between the gold obtained in this way and that extracted from the mines. The latter was called nub-en-set, i.e. gold of the mountain, while alluvial gold was named nub-en-mu, i.e. ‘gold of the river’. Auriferous sand was placed in a bag made of a fleece with the woolly side inwards; water was then added and the bag vigorously shaken by two men. When the water was poured off, the earthy particles were carried away, leaving the heavier particles of gold adhering to the fleece. There is a picture of this operation on one of the buildings at Thebes.

Mercury

Mercury (Greek-hydra gyros, liquid silver; latin-argentum vivum, live or quick silver) is stated to have been found in Egyptian tombs of from 1500-1600 B.C.

Metal and Mysticism

In the early centuries of our era, however, there gradually developed a mysticism among chemical writers due to Egyptian and Chaldean religious magical ideas, and there developed a fanciful relation of the metals as such to the sun and the planets, and as a consequence there arose the belief that it was necessary to confine the number of metals to seven.

Thus Olympidorous-in the 6th century of our era gives the following relation:

Gold – The Sun

Silver – The Moon

Electrum – Jupiter Iron – Mars

Copper – Venus

Tin – Mercury

Lead – Saturn

Metallurgy was by no means the only art practiced with conspicuous success by the ancient Egyptian craftsmen. Glass was almost certainly the invention, not of the Phoenicians, but of the Egyptians, and was produced on a large scale from a very early date.

Glass Making

This art is of very ancient origin with the Egyptians, as is evident from the glass jars, figures and ornaments discovered in the tombs. The paintings on the tombs have been interpreted as descriptive of the process of glass blowing. These illustrations representing smiths blowing their fires by means of reeds tipped with clay. Therefore it can be concluded that glass blowing is apparently of Egyptian origin.