The remains of glass furnaces discovered by Flinders-Petrie at Tel-El-Amarna (1400 B.C.) illustrates the manufacture of rods, beads, and jars or other figures, formed apparently by covering clay cores with glass and later removing the cores.

Egyptian glass articles were of colored glass, often beautifully patterned. Analyses of ancient Egyptian glass articles show that generally glass was a soda-lime glass with rather soda content as compared with modern soda-lime glass.

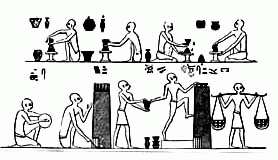

Egyptian Making Pottery, With Furnace Beni Hasan, 1900 B.C.

The given analyses do not differ from those of some soda-lime glasses of modern times. Lead was used in glasses from very ancient times. French scientist analyzed a vase of the Fourth dynasty in Egypt that contained about one quarter lead.

Artificial pearls, made of glass, were manufactured in such numbers that they formed an important article of export trade, and the old legends of enormous emeralds and other precious stones are most reasonably explained on the assumption that the preparation of paste jewelry was widely undertaken.

The earliest glass-works remains of which have been found date from the eighteenth dynasty, and the oldest dated glass object is a large ball bead bearing the cartouche of Amen-Hotep I, now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. The invention of glass blowing, as opposed to the older method of glass-molding, is comparatively recent, dating back only to about the beginning of the Christian era. Sir Flinders Petrie has shown that the reliefs at Beni-Hassan, which were formerly supposed to represent glass blowers are more probably to be interpreted as metalworkers blowing a fire.

Textile and Dyeing Making

The beginning of the art s of weaving and dyeing are lost in antiquity. Mummy cloths of varying degrees of fitness, still evidencing the dyer1s skill, are preserved in many museums.

The invention of royal purple was perhaps as early as 1600 B.C. From the painted walls of tombs, temples and other structures that have been protected from exposure to weather, and from the decorated surfaces of pottery, chemical analysis often is able to give us knowledge of the materials used for such purposes.

Thus, the pigments from the tomb of Perneb (at estimated 2650 B.C.), which was presented to Metropolitan Museum of New York City in 1913, were examined by Maximilian Toch. He found that the red pigment proved to be iron oxide, hematite; a yellow consisted of clay containing iron or yellow ochre; a blue color was a finely powdered glass; and a pale blue was a copper carbonate, probably azurite; green were malachite; black was charcoal or boneblack; gray, a limestone mixed with charcoal; and a quantity of pigment remaining in a paint pot used in the decoration, contained a mixture of hematite with limestone and clay.

So many analyses results made by known scientists all serve to illustrate the character of the evidence furnished by chemical analysis of surviving samples of the products of early chemical industries.

Earliest Chemical Manuscripts of the Chemical Arts In Egypt

Egypt is generally recognized as the mother of the chemical and alchemical arts, but unfortunately her monuments and literature have left little of the early records that explain these arts.

Some of these ideas have been transmitted to us through Greek and Roman sources but the character of these sources do not enable us to discriminate between the matter derived from Egypt and the confused interpretation or additions of the early Greek alchemists.

Much of this has to do with the Hermetic teachings passed down through the ages as part of the mystery school teachings.

Somewhere around 290 A.D. the Emperor Diocletian passed a decree compelling the destruction of the works upon alchemical arts and on gold and silver throughout the empire, so that it should not be the makers of gold and silver to amass riches which might enable them to organize revolts against the empire. This decree resulted in the disappearance of a mass of literature that doubtless would have furnished us with much of interest in the early history of chemical arts and ideas.

There have been saved to our times two important Egyptian works on chemical processes; the earliest original sources on such subjects discovered at Thebes (South Egypt), and both formed part of a collection of Egyptian papyrus manuscripts written in Greek and collected in the early years of the nineteenth by Johann d¹Anastasy vice consul of Sweden at Alexandria. The main part of this collection was sold in 1828 by the collector to the Netherlands government and was deposited in the University of Leyden. In 1885, C. Leemans completed the publication of a critical edition of the texts with Latin translation of a number of these manuscripts, and among these was one of the two works above mentioned.

It is known as the Leydon Papyrus.

The French chemist Marcelin Berthelot who was interested in the history of early chemistry, subjected this Papyrus to critical analysis and published a translation of his results into French with extensive notes and commentaries.

On the basis of philological and paleography evidence, he concluded its date is about the end of the third century A.