Ancient Egyptian Alchemy and Science

The ancient Egyptians had many advanced scientific technologies, with much being found in picture form and in three-dimensional models throughout Egypt. Themes reflecting scientific knowledge and achievement can be found throughout the world in various ancient civilizations. These teachings seemed to center on electromagnetic energies.

Scenes depict scientists of that timeline able to work in fields of alchemy, biology, chemistry, dentistry, anesthesiology, air flight, and the electromagnetic energies of the Great Pyramid among other sacred sites – how that link together and to the sacred geometry that forms our universe. Much of the interpretation is left to those in our timeline to decipher.

Rare squared form of tet, at left. The heavy animal may be a ancient symbol for heavy electrons; the squaring may be an ancient way of referring to water. The tet might employ magneto hydrodynamic principles like ancient Egyptian and modern transportation technology, but it may employ it in obtaining energy from certain materials as well.

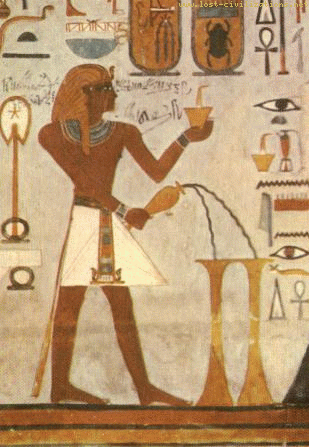

The study of science and medicine were closely linked to religion as seen in many of the ancient rituals. The “pouring” and “anointing” we see in so many Egyptian works is the application of electromagnetic forces and not the application of actual fluids. Much of this was linked with ‘magic’ of some sort – as many unexplained things did occur. These were often considered miracles.

This image implies that something poured into the planet could cause spontaneous growth. The “pouring of water or an offering” and the outlandish angles at which it is being done tends to make it one of countless scenes reinforcing the idea that such scenes are instead showing the migration or transmission of electromagnetic forces. Every sacred symbol – linked to the gods – had a scientific as well as an esoteric purpose.

The cathode-ray tube or “Crookes’ tube” like object depicted in scenes from the temple of Hathor at Dendera may depict a relativistic source of these heavy electrons – which could drastically expedite the magical processes which involve these particular tubes.

The walls are decorated with human figures next to bulb-like objects reminiscent of oversized light bulbs. Inside these “bulbs” there are snakes in wavy lines. The snakes’ pointed tails issue from a lotus flower, which, without much imagination, can be interpreted as the socket of the bulb. Something similar to a wire leads to a small box on which the air god is kneeling. Adjacent to it stands a two-armed djed pillar as a symbol of power, which is connected to the snake. Also remarkable is the baboon-like demon holding two knives in his hands, which are interpreted as a protective and defensive power.

In his book The Eyes of the Sphinx, Erich Von Däniken writes that the relief is found in “a secret crypt” that “can be accessed only through a small opening. The room has a low ceiling. The air is stale and laced with the smell of dried urine from the guards who occasionally use it as a urinal.” The room is not so secret, however, as many tourists visit and photograph the room every year. Von Däniken sees the snake as a filament, the djed pillar as an insulator, and claims “the monkey with the sharpened knives symbolizes the danger that awaits those who do not understand the device.” This “device” is, the reader is assured, an ancient electric light bulb.

Electrical Lighting in Ancient Egypt

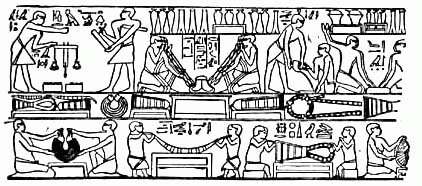

Metallurgy

Metallurgy in particular was carried on with an elaborate technique and a business organization not unworthy of the modern world, while the systematic exploitation of mines was an important industry employing many thousands of workers. Even as early as 3400 B.C., at the beginning of the historical period, the Egyptians had an intimate knowledge of copper ores and of processes of extracting the metal. During the fourth and subsequent dynasties (i.e. from about 2900 B.C. onwards), metals seem to have been entirely monopolies of the Court, the management of the mines and quarries being entrusted to the highest officials and sometimes even to the sons of the Pharaoh.

Whether these exalted personages were themselves professional metallurgists we do not know, but we may at least surmise that the details of metallurgical practice, being of extreme importance to the Crown, were carefully guarded from the vulgar. And when we remember the close association between the Egyptian royal family and the priestly class we appreciate the probable truth of the tradition that chemistry first came to light in the laboratories of Egyptian priests.

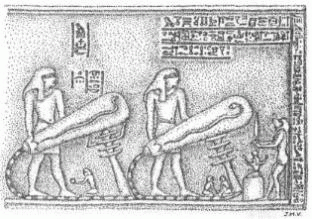

Metal-Workers’ Workshop in Old Egypt

Copper and Iron Extraction

In addition to copper, which was mined in the eastern desert between the Nile and the Red Sea, iron was known in Egypt from a very early period and came into general use about 800 B.C. According to Lucas, iron appears to have been an Asiatic discovery. It was certainly known in Asia Minor about I300 B.C. One of the Kings of the Hittites sent Rameses II, the celebrated Pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, an iron sword and a promise of a shipment of the same metal.

The Egyptians called iron ‘the metal of heaven’ or ba-en-pet, which indicates that the first specimen employed were of meteoric origin; the Babylonian name having the same meaning.

It was no doubt on account of its rarity that iron was prized so highly by the early Egyptians, while its celestial source would have its fascination. Strange to say, it was not used for decorative, religious or symbolical purposes, which – coupled with the fact that it rusts so readily – may explain why comparatively few iron objects of early dynastic age have been discovered.

One which has fortunately survived presents several points of interest: it is an iron tool from the masonry of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza, and thus presumably dates from the time when the Pyramid was being built, i.e.