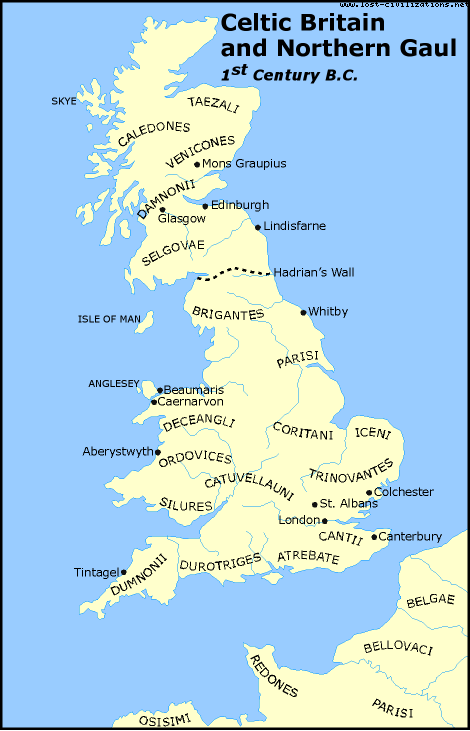

The Celtic settlement of Britain and Ireland is deduced mainly from archaeological and linguistic considerations. The only direct historical source for the identification of an insular people with the Celts is Caesar’s report of the migration of Belgic tribes to Britain, but the inhabitants of both islands were regarded by the Romans as closely related to the Gauls.

Information on Celtic institutions is available from various classical authors and from the body of ancient Irish literature. The social system of the tribe, or “people,” was threefold: king, warrior aristocracy, and freemen farmers.

LANGUAGE

The Six Celtic Languages

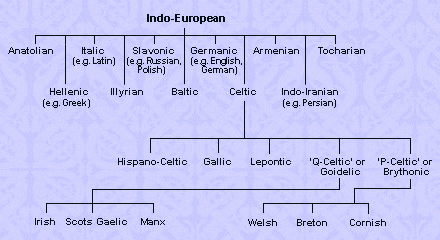

There was a unifying language spoken by the Celts, called not suprisingly, old Celtic. Philogists have shown the descendence of Celtic from the original Ur-language and from the Indo-European language tradition. In fact, the form of old Celtic was the closest cousin to Italic, the precursor of Latin.

The original wave of Celtic immigrants to the British Isles are called the q-Celts and spoke Goidelic. It is not known exactly when this immigration occurred but it may be placed somtime in the window of 2000 to 1200 BC. The label q-Celtic stems from the differences between this early Celtic tounge and Italic. Some of the differences between Italic and Celtic included that lack of a p in Celtic and an a in place of an the Italic o.

At a later date, a second wave of immigrants took to the British Isles, a wave of Celts referred to as the p-Celts speaking Brythonic. Goidelic led to the formation of the three Gaelic languages spoken in Ireland, Man and later Scotland. Brythonic gave rise to two British Isles languages, Welsh and Cornish, as well as surviving on the Continent in the form of Breton, spoken in Brittany.

The label q-Celtic stems from the differences between this early Celtic tounge and the latter formed p-Celtic. The differences between the two Celtic branches are simple in theoretical form. Take for example the word ekvos in Indo-European, meaning horse. In q-Celtic this was rendered as equos while in p-Celtic it became epos, the q sound being replaced with a p sound. Another example is the Latin qui who. In q-Celtic this rendered as cia while in p-Celtic it rendered as pwy. It should also be noted that there are still words common to the two Celtic subgroups.

Today there are no remaining independent Celtic countries; however, the Celtic language (Gaelic) has survived in the form of Scots, Irish, Welsh, Breton, and Manx Gaelic. Irish and Manx Gaelic are the closest to the original language, retaining the Q sound in such words as cen (head), whereas the Breton and Welsh pen (also head) uses a P sound.

THE SERPENT’S STONE

The Serpent’s Stone is a symbol of an ancient wisdom and fidelity; touchstone of universal truths. The complexity of earthly life sometimes obscures a simple truth. The four serpent heads emerge from the labyrinth of Creation to point the way through self-examination. The brilliant colours convey a sense of drama and intrigue. As a meditative glyph, it endorses the need for self-examination. Thus when truth becomes entangled in a moral dilemma, evoke the secret wisdom of the Serpent’s Stone.

WRITING – OGHAM

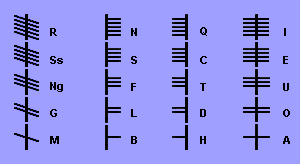

The ancient Celts had a form of writing called ogham (pronounced OH-yam). It was the writing of Druids and Bards. Ogham is also called ‘Tree Alphabet’ because each letter corresponds to a tree and an associated meaning. The letters were, in fact, engraved onto sticks as well as larger standing stones.

In keeping with Druidic concepts, each of the Ogham’s twenty letters bears the name of a tree. A-Ailim (Elm), B-Bithe (Birch), C-Coll (Hazel), for example. The Celts had an oral tradition so it was not used to write stories or history as these were memorized.

The Ogham alphabet contains twenty letters and is read from the bottom up. The letters are constructed using a combination of lines placed adjacent to or crossing a midline. An individual letter may contain from one to five vertical or angled strokes. Vowels were sometimes described as a combination of dots. The midline was, most often, the edge of the object on which the inscription was carved.

Ogham was named after the Celtic god of literature, Ogma. It was used on the edges of burial stones and boundary markers. They usually held the name of a person. Examples exist to this day.

It was also used on rods or strips of wood that were fastened together at one end. These wands were opened and closed to present stories or poems.

Since these wands were made of wood, none survive today. Only the messages on stone survived.

The wooden sticks with the Ogham marking were used for divination similar to the way Runes were used by Norse peoples. Only the Druids and Bards understood the system and could have great influences on their people when they demonstrated its power.

There are 369 verified examples of Ogham writing surviving today. These exist in the form of standing stones concentrated in Ireland, but scattered across Scotland, the Isle of Man, South Wales, Devonshire, and as far afield as Silchester (the ancient Roman city of Calleva Attrebatum).

Similiar markings have been found on standing stones in Spain and Portugal. The markings in Spain are believed to be much older than the ones in Ireland, perhaps dating from 800 BC. It is from this area of the Iberian Peninsula that the Celts who colonized the British Isles may have come.

Ogam can still be seen inscribed on hundreds of large and small stones, on the walls of some caves, but also on bone, ivory, bronze and silver objects. The Ogam script was especially well adapted for use on sticks. Sticks are part of the Basque word for “alphabet”: agaka, agglutinated from aga-aka, aga (stick or pole) and akats (notch).