Not much was known about Bahriyah oasis until a town developed there in the sixth century BC. Its population grew under Greek rule. Alexander the Great built a temple there after he entered Egypt in 332 BC, but the town’s heyday was in Roman times when wine was the chief export.

Today, Bahriya is a tranquil oasis of date groves and hot springs, off the tourist track. Its population has shrunk since Roman times and there are few foreign visitors.

“It was thanks to the wine trade that locals in Bahriya grew rich,” said Hawass. “That’s why they were able to afford such lavish burials. But I think the water here was rich in iron and that killed off many of the town’s inhabitants at a young age.”

June 16, 1999 – Bahriya Oasis, Egypt

Golden Mummies Discovered – ‘Valley of the Mummies’ is the biggest of its kind

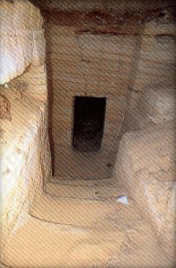

Excavation of the tombs

Archaeologists have found some 105 mummies of high-ranking Roman Egyptians, many wearing gold masks, in the Western Desert.

Entrance to one of the tombs

Archaeologist Zahi Hawass said the mummies, buried more than 2,000 years ago. They were found in April in four tombs in the town of Bawiti in Bahariya oasis, 250 miles southwest of Cairo.

Hawass said the tombs are part of a vast necropolis found in 1993 after a donkey stumbled into it – from above the ground.

The mummies, in porcelain caskets or canvas wrappings, were untouched by tomb robbers even though they were found in an area where villagers collected stone for building.

The mummies are covered with a thin layer of gold and wearing gypsum masks. Sumptuous gilded death masks depict lifelike faces of real people, rather than stereotypical images.

The depictions were of wealthy members of a Greco-Roman civilisation who died in the 1st or 2nd century AD.

Packed tightly in small caves carved into rock, the mummies still bore colorful scenes painted by mortuary artists. One mask showed people bearing offerings to ancient Egyptian gods. Another had a crown with the insignia of Horus, the principal deity of living rulers.

Some of the painted dead looked not at the intruder but at each other – as they had, undisturbed, for almost two millennia. In one corner I saw a touching scene: a woman lying by her husband, her face turned affectionately towards him.

Families of men, women, children and babies rested in death together, some wrapped and embalmed in plain linen but many cased in cartonage, a durable plaster-coated pasteboard of linen and papyrus, with painted faces, elaborately gilded waistcoats and complex religious scenes.

Each mask was different, as were the visages painted on terracotta sarcophagi in an adjoining tomb. Not only had the bodies been preserved, but so had the expressions, even the hairstyles of the dead.

One of the mummies was about five feet in height. She had a beautiful gilded plaster crown with four decorative rows of red curls ending in spirals that framed her forehead and extended behind her ears.

“We didn’t find any names or titles of the deceased but the amount of gold and royal insignia would suggest high political status,” archaeologist Mohammed Aiyadi said.

A trove of items including pottery, copper and jewelry found beside the mummies was being examined to date the mummies more precisely.

“We did find Greek coins but this was because the Romans in Bahriya continued to use Greek coins until new Roman ones came from Alexandria,” Aiyadi said.

Hawass also found mourning statues, images of women, and pottery. Also very common were cheerful statues of the gnome-like Bes, a round-bellied, drolly-leering dwarf whom Hawass calls “the god of pleasure and fun.” Patron of dancers and musicians, Bes also protected households and pregnant women. A meter-high statue of Bes in a corner is the only thing that brightens the atmosphere of the Bahareya Museum’s single exhibition room besides the glitter of the displaced deceased.

The people of Bahareya named Zeszes from the Middle Kingdom onward, but whose name in Greco-Roman times is uncertain – appear to have made a special cult of Bes. A temple dedicated to him was found in the 1980s in the center of Bawiti, the only one ever recorded in Egypt.

One suspects this is because there was a lot of merriment in early Bahareya. For centuries, the oasis was a famous wine-producing region. (Bahareya today harvests a wide variety of fruit, from dates to apricots to, yes, grapes.) Previously discovered wine presses, vats and blenders attest to the happy industry that seems to have supported the oasis’ economy.

Many Greek coins (which the Romans didn’t bother to replace in commerce), were left in the tombs for the dead to use to bribe those who would ferry them to the nether world. Scarabs and jewelry made of carnelian, faience and copper were scattered with the coins. Abundant water, the presence of natural hot springs and a fairly moderate climate (despite being surrounded by some of the most forbidding wasteland on the planet) must have combined to make life in classical Bahareya more than bearable for most people. No wonder they wanted to repeat it after death.

Hawass said the site became a cemetery under Ankkaenre, who ruled from 526 to 525 B.C., but at least two-thirds of the finds in the area were from the Roman era. “The Romans preferred to be buried next to historic and religious sites of previous Egyptians rather than establish a new site,” he said.

“The Romans were clearly in awe of the Egyptians, but it was the Greeks who began to imitate their culture,” Kent Weeks, an Egyptologist at the American University in Cairo, said.