The vision of the afterlife changed.

THE CITY

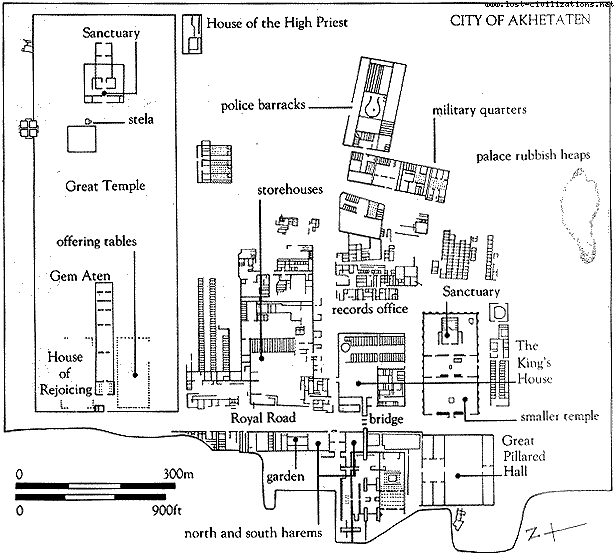

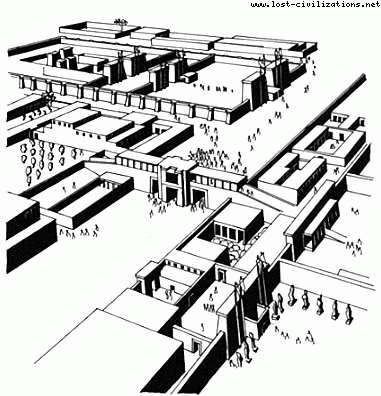

In its finished state Armana offered a theatrical setting for celebrating Akhenaten’s kingship. The city sprawled for miles over the plain. There were elegant palaces, statues of the Pharaoh, good housing throughout the city, a royal road that ran through the center of town, probably the widest street in the ancient world. It was designed for chariot processions, with Akhenaten leading the way.

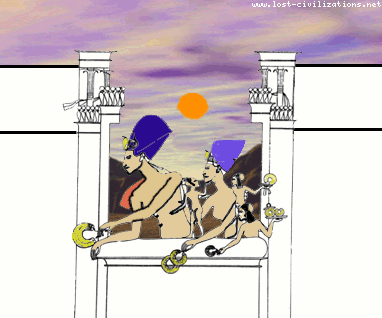

Spanning the road, a bridge connected the palace with the temple area. Akhnaton and Nefertiti appeared before the people on the balcony known as the “window of appearances”, tossing downgold ornaments and other gifts.

THE PEOPLE

At its height the city grew to more than 10,000 people – bureaucrats, artisans, boatmen, priests, traders and their families. Though most were happy, many were not, especially those who did not like to stand in the open sun. Akhenaten worshipers spent lots of time in the sun.

Akhenaten wanted everyone to be happy. He created a beautiful, idealistic religion and Utopia for his people but many just didn’t understand it. Akhenaten was not living in the reality of his worshippers. Though he had found himself and his God but the people were used to Gods they could see, carved in stone with beautiful bodies, many with heads of animals. Akhenaten’s God was too much of an abstraction. Aten was the basic principle of the universe, Light! They also wondered why the sun God only shed its rays on the royal family and not everyone.

According to present evidence, however, it appears that it was only the upper echelons of society which embraced the new religion with any fervor. Excavations at Amarna have indicated that even here the old way of religion continued among the ordinary people. On a wider scale, throughout Egypt, the new cult does not seem to have had much effect at a common level except, of course, in dismantling the priesthood and closing the temples; but then the ordinary populace had had little to do with the religious establishment anyway, except on the high days and holidays when the god’s statue would be carried in procession from the sanctuary outside the great temple walls.

THE END TIMES

Akhenaten lived in his dream in Amarna for ten years as conditions grew worse in Egypt. He remained isolated from the true problems of the people. Akhenaten apparently neglected foreign policy, allowing Egypt’s captured territories to be taken back, though it seems likely that this image can be partially explained by the iconography of the time, which downplayed his role as warrior.

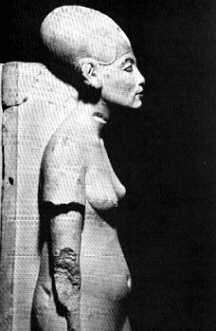

Nefertiti is depicted in her advanced years. She wears a long, white linen dress that allows the contours of her body to be seen. It has been speculated that this small statuette was the model for a life size representation that was never executed. Arnold points out that, although she is past her prime, she is not old. While this may be true, the sagging features of the statuette do indicate that she is no longer the vivacious Queen.

In 1335 BC Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s wife and companion, is said to have disappeared most likely died. His mother Tiy had also died as did his minor wife, Kia. That combined with the loss of his daughter made Akhenaten feel alone and depressed.

Nefertiti’s disappearance coincided with the sudden appearance of a young man named Smenkhkare. Smenkhkare, who was given the same title (Neferneferuaten) as the now vanished Nefertiti, was crowned co-regent to Akhenaten when he (Smenkhkare) was about sixteen. He was married to Akhenaten’s eldest daughter, Merytaten.

There is uncertainty about the relationship between Akhenaten and his successors, Smenkhkare and Tutankhamun. The biggest mystery associated with Smenkhkare was where he came from. It is possible that both he and Tutankhamun were Akhenaten’s sons by another wife, possibly Kiya who was ‘much loved’ of the Pharaoh. As there was inbreeding to keep the line pure we may never know the relationships within their family.

It is also a matter of great controversy as to whether or not Smenkhkare continued to reign after Akhenaten died. According to Dr. Donald Redford, a professor of Egyptology and the director of the Akhenaten Temple Project, Smenkhkare may have succeeded Akhenaten by a short while, during which he made half-hearted attempts at going back to the old religion (something which probably wouldn’t have happened while Akhenaten was alive). Another thing that suggests that he outlived Akhenaten are references to him made in certain tombs. He was also buried in the old capital.

But here one has to consider the way Akhenaten behaved concerning those people who were known to be his children. Every one of his six daughters, whenever referred to in writings from the period, was repeatedly called ‘the king’s daughter, of his loins, (daughter’s name)’.

In Egypt, as with any other kingdom of the ancient or not so ancient world, male heirs were much desired. If Akhenaten had a son, he almost certainly would have repeatedly said so.

Cyril Aldred, a prominent Egyptologist who has written several books about Akhenaten, uses the argument that Smenkhkare must have been born three years before Akhenaten’s reign began, thereby reducing the likelihood of his being Akhenaten’s child.