Sarmat tribes on Ural

In the epoch of Early Iron (1-st millenium B.C.- the middle of the 1-st millenium A.D.) wide Eurasian steppes from Mongolia in the East to Pannonia in the West were inhabited mainly by nomadic Iran-spoken tribes, which had common name – Early(ancient) nomads.

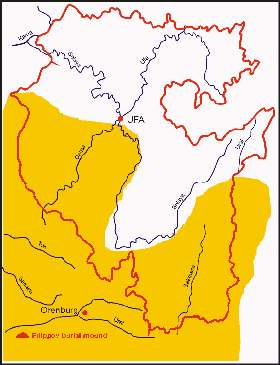

Written sources of ancient authors, mainly Greek and Roman, mention many tribes, which inhabited the steppes of Eurasia in the epoch of Early Iron. Kimmeris, scythians and meots in the North beach of the Black Sea, massagets, sakas and usuns in the steppes of Kazakhstan and Middle Asia were the most famous and numerous among them. the tribes of savromats and their descendants sarmats, which led a normad’s life in the steppes of the South Urals and Low Volga area, were one of great unions of nomads in that period, which were mentioned by ancient authors.

History and culture of savromat and sarmat tribes, as well as their west and east neighbours scythian, sako-massagetic, scythian-siberian tribal unions are comparatively well-known due to rich and many-sided archaeological material, and also a few ancient written sources. The available information shows that the society of ancient normads was at the stage of decomposition of primitive communal relations, forming of early-class state unions. Property and social stratification of nomads strikingly appeared in magnificient funeral structures with high-skilled jewelry. Scythian “tsar” barrows of Northen Prichernomorie such as Solokha, Chertomlyk, Kul-Oba, Tolstaya Mogila and others became famous throughout the world. Pazyryk, Bashadar and Tuektin barrows of Altai, Besshatyr barrows of Semirechie, “Ardjan” barrow in Minusinsk hollow and “Issyk” barrow near Alma-Ata with its “gold” man acquired no less fame.

Among savromat and sarmat antiquities of the South Urals and Low Volga area comparatively large barrows that reached the height of 2-3 metres and more were investigated as well. In spite of rich finds they could not be compared with the barrows of Scythian and Sako-massagetic nomadic aristocracy. It gave many scientists the reasons to consider that property and social stratification in the nomadic society of the Urals and Povolzhie had not acquired such perceptible scale as it was in Prichernomorie, Middle Asia, Kazakhstan and Altai, and that sarmat and savromat tribes were in a lower stage of economic, social and cultural development with their West and East neighbours.

The central Filippov barrow is dated by the beginning of the IV-th century B.C. and belongs to Early-Sarmatian (Prokhorov) culture. The most reasonable argument testifyed to this data is an iron two-blade sword found at the bottom of dromos with other articles of weaponry and harness. The sword has a straight navershie, bent at obtuse angle crossing and, according to Smirnov’s classification, it belongs to so-called transitional type (from Savromatian to early-Sarmatian). K.F.Smirnov convincingly showed that all swords of such type are dated by the IV-th century B.C. Gold plates of wooden dishes from Filippovka (in their form, subjects and manner of making) have much in common with analogous things from Sarmatian memorials of the Don river,”tsar” barrows of Scythia, which are dated by the IV-th – the III-rd centuries B.C. There are much resemblance between ceremonial weaponry of central Filippov barrow (the sword and the dagger) and the weaponry of Sakian barrow Issyk. They repeat each other in the form of navershies and crossings of gold encrustation of the handles and, undoubtedly belong to one and the same time. But it is not the V-th century B.C. as the explorer of the barrow Issyk K.A.Akishev suggests, but later period – the IV-th century B.C.

Materials of other investigated Filippov barrows have important meaning for dating of the central barrow. 17 barrows from 25 were investigated. On the whole, both burial ceremony and objects of the barrows are identical. They all were erected in one and the same time , at least in 30-50 years. Only one grave (grave 2, barrow 23) dated by more ancient time, probably the V-th century B.C.,is an exeption, which is seen in the objects and in stratigraphical data. The material of other graves doesn’t deviate from the framework of the IV-th century B.C.

Among the articles of weaponry the iron swords of “transitional” type – straight or bent navershie and bent at obtuse angle crossing – are the most reliable material for dating. They were found in two central graves of the barrow. Bronze mirrors with long handles and wide bulge along the edge are characteristic for the beginning of the IV-th century B.C. They were also found in two graves. Bridle collections decorated with bronze plates in wild-animal style, remains of quivers with iron and bronze three-blade tips of arrows, temporal pendants and various beads presented in Filippov barrow also belong to the IV-th century B.C.

It must be emphasized that some investigators suggest more ancient dating of Filippov barrow, at least its central barrow – the V-th century B.C. Really, some objects such as silver rhytons, gold two-handle jug, iron swords and daggers with crossing in the form of a butterfly have many analogies in complexes of the V-th century B.C. However we must take into account that gold and silver dishes might be in use for rather long time. The time of its making and putting into the grave might not coincide. The swords with crossing in the form of a butterfly are not strictly dated by the V-th century as well, as they are frequently found with the swords of “transitional” type, which undoubtedly refer to the IV-th century B.C. The necessaty of more accurate definition and even revision of dating of the materials of Savromat-Sarmatian time in South Urals has come to a head. It especially concerns the articles of weaponry.

Fillipov burial ground , especially its central barrow is undoubtedly a prominent memorial of ancient nomads’ culture in South Urals. It is a nekropol of generic and probably tribal clan, which occupied high positions in leadership of military alliance of ancient South Urals’ tribes on the border of the V-th and the IV-th centuries B.C.

At the same time, the discrepancy in dating of the central barrow and the burial ground as a whole (the end of the V-th century B.C., the border of the V-th and the IV-th centuries B.C., the beginning of the IV-th century B.C.) does not have important meaning because it does not influence on determination of place and role of the tribes, which left us this memorial, in historical events in Eurasia in Scythian time.