Because the sun sets in the west, where it was believed to enter the underworld, the goddess was associated with the necropolis and helped the dead make the passage from this life to the next. As such, she often appears in tombs and on coffins.

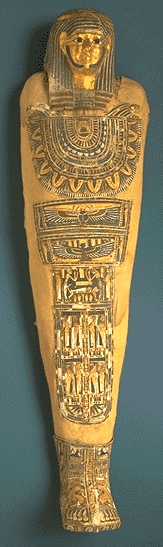

Below an elaborate collar, a winged goddess with a sun disk on her head kneels with arms outstretched to protect the deceased. Beneath her, the mummy of the deceased lies on the lion bed that was used in the ritual embalming. Under the bed are four canopic jars to hold the viscera, with stoppers carved in the form of the four sons of Horus. These beings appear again on the lower part of the lid with mummiform bodies. Between them are five columns of text. The outer two identify the figures, and the three middle ones contain the traditional offering formula asking for a series of benefits for the deceased in the next life. The name of the owner would have been included at the end of this text but is now lost through damage. Figures of Anubis, the god of embalming, in the form of two black jackals lying on pedestals decorate the foot of the coffin.

This fragment of temple relief comes from a scene that would have shown the king offering to a standing or seated deity drawn on the same scale. The roundly modeled high relief used here began to appear during the Late period and reached its peak under the Ptolemies. Unfortunately, the royal cartouche is too damaged for the name of the king to be identified lid depicts the deceased as a mummy wearing a divine, tripartite wig and the long, braided beard associated with Osiris, god of the underworld, with whom the deceased is identified.

The Book of the Dead is a funerary text that emerged in the New Kingdom as a descendant of the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts of the Old and Middle Kingdoms respectively. Its function was to secure a successful passage into the afterlife for the deceased through the spells and images it contained. The fragment illustrated here was cut from a larger roll. The text is from chapters 1 and 72 of the Book of the Dead and is written in cursive hieroglyphs drawn in black ink within vertical columns reading from right to left.

Depicted above is part of a painted scene or vignette showing the funeral procession to the tomb. The procession moves to the left. On the left of the scene is Anubis, the jackal god of embalming, on a shrine. In the middle, a priest drags the canopic chest containing the viscera of the deceased. On the right is a line of women mourners. Two of them, facing one another, display the characteristic gesture of mourning, which consists of raised arms and backward-facing palms, as though beating the forehead or casting dust over the body. Between the two women stands a small male figure who may be Paheby, the owner of the papyrus. If the fragmentary scene had been complete, Paheby’s sarcophagus would have been seen at the head of the procession.

In order to enter the afterlife, it was important that the deceased have a proper burial with all the correct rituals and traditional funerary equipment. First, the body had to be preserved through mummification, a process by which it was artificially dehydrated and then wrapped in linen bandages. The invention of mummification may have stemmed from the initial practice during predynastic times of burying bodies directly in the ground. The preservative properties of the hot, desiccating sand may have suggested to the Egyptians that survival of the body was necessary for continued existence in the afterlife. Later, in the Early Dynastic period, when the body was no longer directly surrounded by sand but was placed in a specially constructed burial chamber, the natural processes of decay set in. When they discovered this, the Egyptians over the course of centuries developed a way of keeping the body intact using resins and the naturally occurring salt, natron.

The mummy here has been shown by X-rays and CAT scans to be that of a middle-aged man. His name is not known. The body, wrapped in bandages with arms at the side, is enveloped in a linen shroud, over which are placed trappings of cartonnage, consisting of layers of linen stiffened with plaster that could then be painted. A mask with a gilded face, identifying the deceased with the sun god, covers the head. Below it, a chest panel is decorated with a broad collar, and below that another panel carries a winged scarab beetle and a kneeling figure of the sky goddess with outstretched wings surmounted by the hieroglyphic sign for “sky” painted in blue. A third panel, covering the legs, contains a scene showing the mummy on a lion bed mourned by the sister-goddesses Isis and Nephthys, below which are a series of mummiform figures representing the different forms of the sun god in the underworld. Figures of the jackal god Anubis appear on the foot covering, and the toes are depicted in the form of rearing cobras, with sun disks on their heads representing toenails.

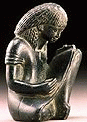

Seated Scribe

Of the materials used by the Egyptian sculptor – clay, wood, metal, ivory, and stone – stone was the most plentiful and permanent, available in a wide variety of colors and hardness. Sculpture was often painted in vivid hues as well. Egyptian sculpture has two qualities that are distinctive; it can be characterized as cubic and frontal. It nearly always echoes in its form the shape of the stone cube or block from which it was fashioned, partly because it was an image conceived from four viewpoints. The front of almost every statue is the most important part and the figure sits or stands facing strictly to the front. This suggests to the modern viewer that the ancient artist was unable to create a naturalistic representation, but it is clear that this was not the intention.

Art was used as a medium to decorate religious shrines.